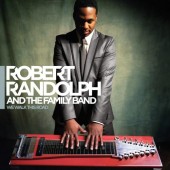

Robert Randolph ~ We Walk This Road Artist Notes

This record is a celebration of African-American music over the past one hundred years and its social messages from the last thirty. Although we cover a whole timeline of different eras on We Walk This Road, what ties these songs together remain their message of hope, their ability to uplift.

After we finished our last record, Colorblind, we began searching for a great producer to help guide the follow up. We wanted someone who understood me and the road I’ve walked this far, who understood our connections of my roots within rock and gospel and the church, who would help us put those things in their most compelling context.

T Bone Burnett shared the vision of how gospel, blues and rock could be put together in a way that could relate to my history and connect to my present. It was important to us that we make the record we wanted to make, even if the end result was unclassifiable. We just focused on making great songs and great music that spoke to me, and that reflected the way I try to speak to the world.

We recorded We Walk This Road over about two years, after T Bone had finished his record with Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. We went into the studio with virtual libraries of songs, whole volumes worth of material to go through. T Bone brought in old archival songs from the twenties and thirties and many of them were in the public domain. I had songs that I had written with the band, or that other artists had sent me, and we sat down and starting sifting through history.

When we found something we liked, we would either cover it or re-work it using our own words or melodies. Through this creation came an education. T Bone opened a lot of doors for me serving as a link between the past and the present. He knows how to take something from the past and bring it into the present while still allowing the artist to make it his own, in the same way that Hendrix took Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” and made it belong to him.

T Bone listens to music that our grandmothers would listen to as children–not even music that our fathers listened to, but songs that go even further back.some from Gospel and Christian blues, the music that people working in fields across the south likely sang nearly a century ago. Those are the real roots of rock and roll, where everything else comes from.

I was only allowed to listen to modern Christian and gospel music growing up, so there was so much I didn’t know about. My mind is expanded now. The record is finished and I still feel as if I’m not done. I’ve spent over $5,000 on iTunes in the past eighteen months just catching up. Before this record, I didn’t sift through music past the Seventies. I didn’t know about Blind Willie Johnson, or Chess Records. I thank T Bone for being a tour guide into the deepest parts of my musical roots.

We connected the last one hundred years of African-American music in the way people used to: You write your own songs, you cover other people’s material, you re-work older songs. We had some amazing people come in to help. Leon Russell came by to hang out and wound up playing piano on the last track, “Salvation.” Ben Harper plays guitar and sings on “If I Had My Way.” The base of that song came from Blind Willie Johnson, and it was really difficult to get right. It was a country tune for a while. I had honestly given up on it. But Ben came down and said, “Let me get in there! I know just what to do!” He went in there and smoked the choruses, and I thought, “Now we’ve got a tune.” It’s one of my favorite songs on the record.

Where We’ve Been

I grew up in the House of God church. The pedal steel was a big part of our church tradition. I grew up watching older guys play, and I started playing when I was fifteen. When I was nineteen, someone gave me tickets to a Stevie Ray Vaughan concert. After that, I wanted to play pedal steel like Stevie Ray played his guitar. I wanted to take another path than the people who played traditional pedal steel to take it to a whole new level.

We started playing and touring around New York City in 2000, playing clubs like Wetlands, and things started to take off. We were selling out large New York clubs with no record deal, and it started to spread to Philly and Boston. Soon, we signed to Warner Brothers, and word began to get around about us nationally. Great artists like Eric Clapton and Dave Matthews and B.B. King accepted us. Young artists, too: we toured with the Roots and Pharrell and John Mayer. We have been fortunate to be accepted by a wide range of fan bases, and we have been able to build from there. I definitely feel as if everything has been working up to this moment, to this record.

Where We’re Going

I’m very excited to play these tracks live. Those people who have been our fans and followers should see the progression from our last record to this one, and the road we’ve taken won’t seem too foreign to them. When people come to see us, they know that it’s really about the message, about making them feel good. Hopefully, this record will inspire them in the same way. It certainly makes me feel happy. I can’t see myself recording depressing lyrics, lyrics that leave people without a sense of hope. It’s not in me to use the power of the microphone to make music like that. That’s why this record is uplifting - it’s got great messages. It’s all there.

My goal is to open the door for people, in the same way that musical doors have been opened for me. I want to take this musical history and make it relevant to give people a better idea of who I am and where I came from. I think even though I’m a young guy who was born into the era of hip-hop and contemporary gospel, I can help bridge the cultural gap between people who are seventy-five years old and kids who are fifteen years old by reaching back into this history of music.

We Walk This Road was done in our belief in what we all need right now: young voices saying something positive without preaching in hopes of inspiring people. When you stick to what you believe in, and with the roots of where you come from, things will always work out.