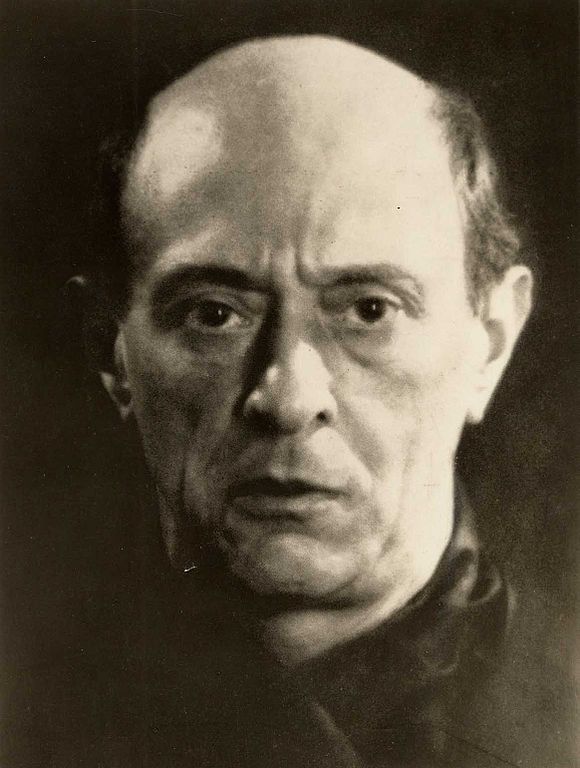

This Week in Classical Music: September 26, 2022. Schoenberg, Part III, from WWI to Nazism. We ended our previous entry on the life of Arnold Schoenbergas the world was  inexorably descending into the madness of war. Schoenberg was 40 and not very healthy, as he had been suffering from asthma for years. As the war started in August of 1914, his teaching income evaporated. A patron (one Frau Lieser) offered him free board in Vienna (as it turned out, for a rather short period), where he moved later in 1914. Much of the European intelligentsia went mad with national and military fervor, denouncing the enemy and expecting their side’s win in a matter of months if not weeks. Schoenberg, unfortunately, wasn’t an exception: he supported the war against France and in a letter to Alma Mahler, Gustav’s widow, wrote: “Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers” (referring to the music of Stravinsky, who then lived in France, Ravel and, for some reason Bizet) “into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.”

inexorably descending into the madness of war. Schoenberg was 40 and not very healthy, as he had been suffering from asthma for years. As the war started in August of 1914, his teaching income evaporated. A patron (one Frau Lieser) offered him free board in Vienna (as it turned out, for a rather short period), where he moved later in 1914. Much of the European intelligentsia went mad with national and military fervor, denouncing the enemy and expecting their side’s win in a matter of months if not weeks. Schoenberg, unfortunately, wasn’t an exception: he supported the war against France and in a letter to Alma Mahler, Gustav’s widow, wrote: “Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers” (referring to the music of Stravinsky, who then lived in France, Ravel and, for some reason Bizet) “into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.”

During the war, Schoenberg was conscripted several times, usually being released soon after because of his ill asthma. He was composing very little; one piece he was working on for years (and never finished) was the oratorio Die Jakobsleiter (Jacob’s Ladder), the libretto for which he completed in 1915. Here’s Grand Symphonic Interlude from Die Jakobsleiter, performed by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Kent Nagano conducting,

In Berlin, the Schoenbergs were struggling financially, and, once Frau Lieser’s generosity was over, the family had to move to cheap boarding rooms. Still, Schoenberg managed to establish a music seminar, which gained some prominence, and in time, after the war was over, the seminar grew into the Society for Private Musical Performances. The Society existed till the end of 1921, when the post-war hyperinflation wiped out much of the donor’s money. It was an amazing undertaking, which could’ve never existed today. The music, selected by Schoenberg himself, but usually not his own, was from the period “from Mahler to the present” and included, among other, works by Bartók, Busoni, Debussy, Korngold, Mahler, Ravel, Reger, Satie, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg’s students, Berg and Webern. Each work was rehearsed and often repeated in different performances; difficult pieces were sometimes repeated during the same concert. Only paying members of the Society were admitted to the concerts, but the payment was voluntary, as much as one could afford. The Society gave 117 concerts, playing 154 different works in 353 performances (so the music was repeated twice on average).

With peace in Europe, Schoenberg’s fame (and notoriety) grew. He was made president of the International Mahler League in Amsterdam and conducted many concerts across Europe. Also, in 1923 his wife Mathilde died. Even though the marriage never recovered after her 1908 romance with Richard Gerstl, Schoenberg was deeply pained. Soon after, though, he married Gertrud Kolisch, the sister of his pupil, the violinist Rudolf Kolisch (Kolisch performed at the Society’s concerts, and later, once the Society was dissolved, he founded a quartet which often played the music of Schoenberg and his students).

In 1926 Schoenberg was offered a position at the Academy of Arts in Berlin, previously occupied by the recently deceased Busoni, and he moved to Berlin for the third time. This was also a time of active artistic development, as Schoenberg transitioned from atonal music to the newly invented 12-tone system, sometimes called “serialism” (we’ll write about this another time). Here’s one of the pieces from that period, the first large-scale serial work, Variations for Orchestra, op. 31. Daniel Barenboim conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Even though the third Berlin period was mostly comfortable financially, the rising antisemitism was affecting the lives of all German Jews, Schoenberg’s included. In 1933 he resigned from the Academy of Arts, left Berlin, moved to France and soon after to the United States.

| Source: | https://www.classicalconnect.com/node/13787 |

| Website: | Classical Connect |